Where Do Zombies Get the Blues: Love and Supermodernity in Jonathan Levine’s Warm Bodies

I will be presenting this paper at the conference:

Oh! The Horror!: The Supernatural in Literature, Film, and Popular Culture

Pennsylvania College English Association 2014 Conference

October 3-4, 2014, State College, PA

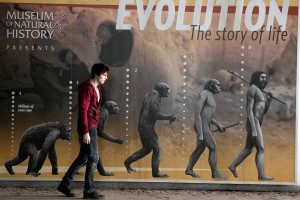

Many critics praised the zomromcom Warm Bodies (Jonathan Levine, 2013) for its originality in evoking Romeo and Juliet, although other classical pieces of literature have recently been interpreted with major zombie or vampire romance elements. In this study, I argue that the innovative aspect of Warm Bodies lies in the environment in which romance between different species (the zombie R and the teenager Julie) takes place. Levine’s film engages with representation of supermodernity in a post-apocalyptic world, addressing the question of where do zombies get the blues. Historically, zombies belong to the outskirts and peripheries of town. In this sense, Warm Bodies is part of to the tradition initiated by Dawn of the Dead (George Romero, 1978), often remembered for its Monroeville airfield sequences and the mall at the edge of Pittsburgh (PA). However, rather than falling into nihilism as its predecessor, Levine subverts the zombie mythology from within, displaying an optimistic happy ending. At the beginning of Warm Bodies, R is lost in an airport, a space that is now stripped of its architectural meaning. Several tracking shots show blank screens, which once provided crucial information on the transmissions of a globalized and networked society. In the digital age, individuals were at once more connected and isolated than ever. R’s voice over comments on all this with a caustic irony that recalls the writings of architect Rem Koolhaas (“Junkspace”) and anthropologist Mark Auge (the so-called “non-places”), while the soundtrack appropriately echoes Brian Eno’s Music for Airports. If Romero’s Dawn of the Dead was a satire of consumerism’s ability to devour us, Warm Bodies offers an insight on our digital present. In the zomromcom, re-humanization occurs through communication that happens thanks to the common ground provided by residual old media. After having eaten the brain of her boyfriend, the voiceless R rescues Julie from the rest of the pack and takes her back to a cluttered 747 aircraft to keep her safe from other attacks. The plane is full of cultural artifacts, which allow them to communicate and eventually fall in love. R plays his collection of vinyl by Guns and Roses, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen, and we also see that he possesses a DVD edition of Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979), famous for its artisanal special effects. French philosopher Gilles Deleuze recognized the cinema as a brain, or brain-body, and in Warm Bodies consuming brains allows the zombies to access their memories. Levine idealizes our immediate pre-digital past, in sepia tones and with Polaroid cameras. In this sense, critics may have missed the point when they complained about the mediocre digital special effects of the Bones (zombie skeletons). Undoubtedly, Warm Bodies’ special effects are not visually stunning, but I argue that this failure to embrace new technologies only reinforces the film’s contents, and is functional to the transition from a disembodied to an embodied and humanized romance.

Leave a Reply